Alleviating car dominance in small to medium sized cities

Toward a more ecological, climate, and people friendly city, Brandon, Manitoba, part 1

Brandon is a small to medium sized car dominant city in the southwestern corner of Manitoba. I was born in Brandon and lived there until I turned twenty eight. The city has problems similar to many urban areas across North America and Europe. Downtown has been undergoing a slow death and the suburbs are expanding outward. Agricultural land and wilderness are paved over — destroying wildlife habitat, accelerating mass extinction and biodiversity loss, and eroding the potential for local food security. Some Brandonites are wealthy, others live in poverty. Homelessness and methamphetamine use have become highly visible since the COVID-19 pandemic, along with rising fear, possibly due to poor (sub)urban design and the absence of street activity — the spatial vapidness of suburban landscapes. Brandon’s suburbs are built for cars and not compatible with a well functioning public transit system. Failure to end car use pumps more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than necessary. Cities need strategies for creating successful compact, diverse, car-free, walkable/bikeable neighbourhoods with high population densities, and easy access to a well functioning public transit network. The spatial footprint of cities must be scaled back to restore the capacity for local food production and wildlife space, while providing adequate and just housing for a growing population. Here I propose a neighbourhood design strategy aimed at reducing car usage in Brandon. It is built upon my previous posts that argue climate and ecological action means working less, consuming less, and embracing a slower, more convivial pace of living, embodied in the concept degrowth. Focusing on the city alone cannot and will not phase out cars. People drive to the city from the rural surroundings on a daily basis and urbanites need to leave the city too. I will write about a regional transit plan for Southern Manitoba later.

Brandon’s public transit system is unicentric. This means all bus routes end in the downtown terminal and trips across the city require a layover and transfer. Transit service is superior in the downtown, but inadequate everywhere else. Trips that take only seven minutes by car, or slightly more by bicycle, may take thirty minutes by bus. Most routes are unidirectional and run every thirty minutes or hour. Stubbornly anti-car and unimpressed by the bus service, I would mostly walk the four kilometres to BU (Brandon University) in the early days of my studies1. When it was raining, I reluctantly took the bus and walked from the downtown terminal (±1.5 kms). Walking took about the same amount of time, as long as the bus wasn’t late. Oftentimes it was. The ride home was direct, but the bus stop stood 550 metres from my house. I dreamed of a transit route directly to and from the university. It would be a simple north-south line along 18th Street, a highway masked as a street that cuts across the city. I finished my studies at BU and left Brandon a few years later, but still I think back upon what could be done to make public transit work for small to medium sized car dominant cities like Brandon. Recently I’ve heard from an ACC (Assiniboine Community College) teacher that the bus to the college is frequently overcapacity causing many students to be late for class. Brandon Transit’s approach isn’t working and it’s hurting those who depend on it. The shortcomings of a system feeds negative perceptions, discourages use, and pushes people into the waiting arms of the auto industry2.

A well functioning public transit system is not a panacea, but offers a partial solution to climate change and the cost of living crisis. If individual car trips are replaced by collective bus rides, greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) will be reduced, better still if most people walked, biked, or the streets were safe enough for wheelchairs. In Manitoba the leading source of GHG is transportation, accounting for 37% in 2022. Car ownership costs on average $10,452 a year, according to a 2023 CAA (Canadian Automative Association) report. A monthly Brandon Transit pass costs an outrageous $1,032 per year. To get people riding the bus, all barriers need to be removed, cost included3.

Banning cars, improving public transit, and renovating public spaces to support active transportation benefits general health and ecosystems. Cars produce environmental stressors like noise, light, and air pollution. Traffic noise has been linked to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, sleep disorders, stress, causes annoyance and pre-mature death; exposure to car exhaust increases the likelihood of cardiovascular diseases, lung cancer, asthma, and pre-mature death — drivers and passengers are exposed to harmful particles at higher rate inside cars; light pollution causes cancer, metabolic disorders, mood disorders, sleep disorders, depression, and obesity. Car tires, and other abrasive parts, shed more carcinogenic particles into the environment than car exhaust — bad news for the ecological benefits of electric cars4. In 2022 alone there were nearly 2,000 car related fatalities in Canada, and almost 120,000 injuries, about 9,000 of those were categorized as serious5. A ban on cars eliminates any chance of death or injury related to car accidents. According to a study in the Atlanta, Georgia area, every hour spent in a car correlates to a 6% increase in obesity, while each kilometre spent walking reduces the risk of obesity by 4.6%6.

Landscapes of impermeable asphalt surfaces like parking lots and streets lowers the capacity of the ground to absorb water during rainfall and snowmelt, increasing the risk of flooding. Asphalt surfaces intensify the urban heat island effect. Parking lots and streets become heat sinks, exacerbating negative mental and physical health outcomes, risking fatalities during heat waves7. Heavy rains and heat waves are expected to occur more frequently at higher intensities as climate change worsens. Banning cars is preventative healthcare and climate change mitigation rolled into one, alleviating the burden cars have on public health care systems while scaling back our collective ecological footprint. Stringent reductions in car traffic would see roadkill and ecosystem fragmentation drastically decline, allowing wildlife and people to move more freely.

Car centric spatial designs produce car dominance and dependency. Car dominance is the strength the automotive industry has over an area, and can be measured by how embedded the automotive industry is within the local, national, and global economy. It has a profound impact on physical space and social norms — parking lots, freeways, and the rules of the roads act as barriers to pedestrian mobility, shaping and controlling human behaviour. Car dominance reinforces car dependency — the inability to travel without a car. I lived in Brentwood Trailer Court which is completely surrounded by roads without sidewalks or bike paths leading into the rest of the city. I would walk through the parking lot of an automotive dealership and a drainage ditch squeezed between a service road and a fenced farm implements dealership. In the ditch I had the feeling that drivers judged me as trailer trash too poor to be in a car. On a few occasions they hurled insults as they drove by. Brentwood is an example of an excluded neighbourhood physically segregated from the rest of the city by roads. From the beginning and to this day, the city decided that the people of Brentwood are not worthy of a sidewalk, and that kind of negligence feeds car dependency. Subjectivity plays an important role. For an active person one kilometre is a short walk, but others will not entertain the idea of walking even that distance. Car dominance and dependency are woven together in an overarching car culture exemplified by choosing to drive a car habitually and think nothing of it, and the idea of cars as status symbols. According to car culture, people without cars are social failures.

Governments under the hypnosis of car culture invest heavily in car infrastructure. Active transportation projects in car dominant cities are merely recreational, such as the Brandon Bicycle Loop that encircles the outskirts of the city — most heavily used in the affluent west end. Public transit is seen as a burden on taxpayers. When austerity strikes, funding for public transit is cut and active transportation projects are put on hold or cancelled. Money flowing into streets, roads, and highways never stops and during times of economic downturn major infrastructure projects (like highways) increase to stimulate economic growth and create jobs. Though the balance appears to be tipping toward public and active transportation as cities and countries implement GHG reduction strategies, electric vehicles are greenwashing the image of cars, providing new justifications for the maintenance and expansion of car infrastructure.

Car dominance and dependency are a entangled in a vicious cycle. The more car dominant the landscape, the worse the conditions for public and active transportation become, and the more people are ensnared in car dependency. People seeking healthier, ecological alternatives struggle against the grain and risk being mangled by cars. Breaking the cycle of car dominance requires a new approach that seeks to convert car dominant neighbourhoods into car free zones connected by free public transit.

Urban Form, Human Behaviour, and the Effectiveness of Public Transit

Urban form plays a crucial role in the perpetuation of a reliable and adequate public transit system. When a city is a suburban maze, destinations are few and far between. Transit routes become too complicated to be effective, travel times are long, and riders must study the routes carefully to figure out how to get to their destination. Low density neighbourhoods are unlikely to need constant transit service, which becomes excessive, i.e., more buses than passengers, or insufficient, i.e., buses unavailable when people need them, because they run only every hour or less.

In a car dominant society, jumping into a car is all too easy. Road rage, traffic jams, the risk of an accident, and the cost of fuel should demotivate drivers, but these are beyond the immediate experience of entering the car, turning it on, and having control over it. Perhaps more importantly is the status symbol of the car and how it makes the driver feel. Catching the bus requires more immediate effort and organization: knowing the transit schedule, getting to the bus stop, and being there at the right time, but in the big picture of urban life, a decent public transit system can makes life easier and reduces stress. It may require modesty, patience, and empathy — to understand that abandoning the car in favour of public transit is more compatible with climate change mitigation, ecological conservation, and high quality public spaces.

Access to public transit has to be made as easy as possible to convince people to ride. Routes should be direct. Riders shouldn’t need to memorize schedules, but simply walk to a transit stop, check the sign that says when the next bus will arrive and whisper, “Look at that! Only three minutes until the bus comes”. If the bus runs every two to ten minutes, the need to memorize a schedule vanishes. When it’s longer than a ten minute wait, riders are more likely to seek other ways of getting around.

Compact, diverse, and population dense neighbourhoods sit at the foundation of an effective transit system. A diverse neighbourhood has a mixture of spaces for living, working, making, gathering, and consuming. Designated public transit infrastructure and limitations, or outright bans, on cars only help to improve transit service, as traffic jams are the usual causes for bus delays. A solution is to concentrate uses and housing into self-sufficient urban villages (or centres). The public transit system only needs to connect these centres to one another following a polycentric approach.

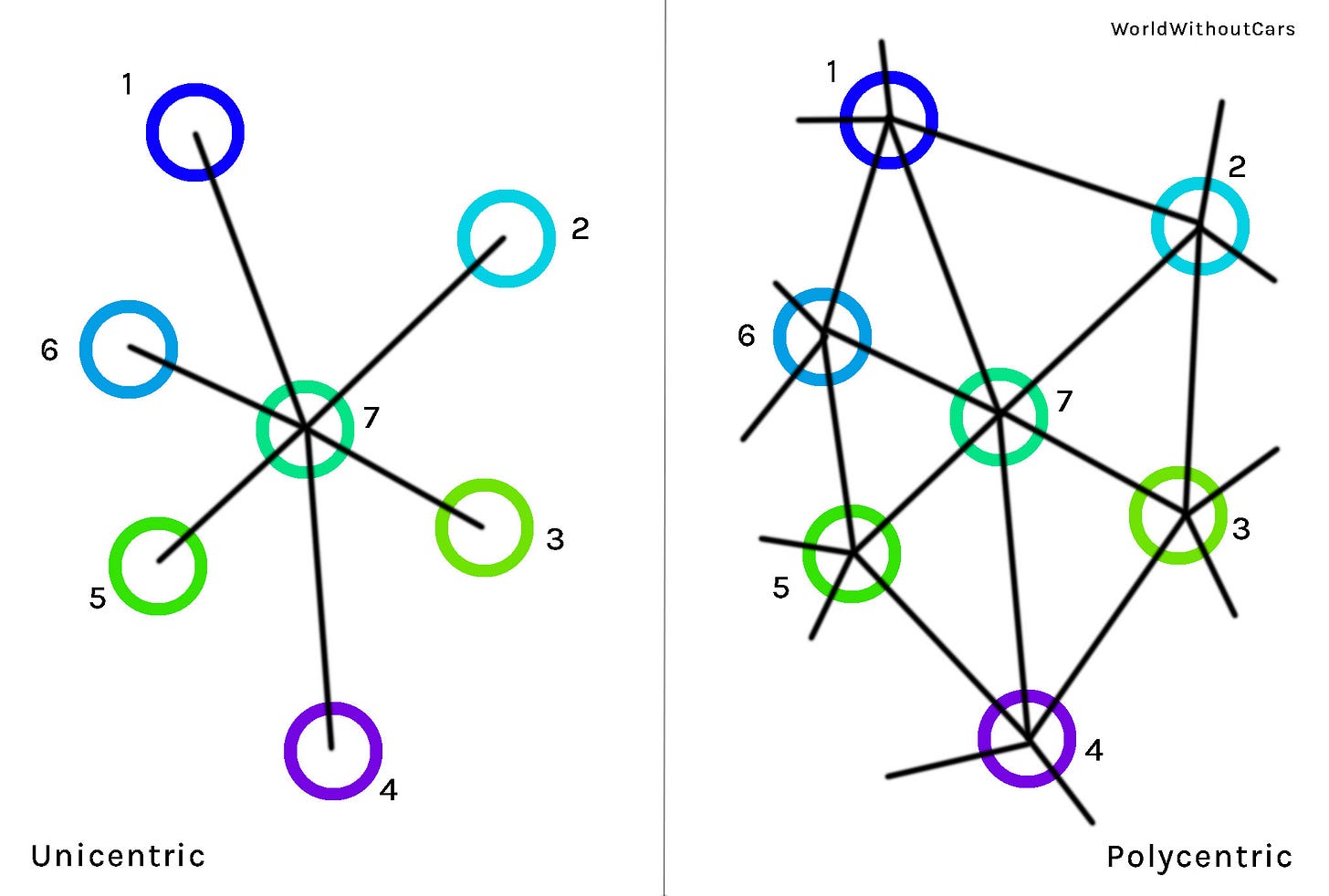

The above diagram illustrates a simplified unicentric transit model on the left and a polycentric model on the right. For the unicentric model, all of the outer circles (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) are connected only to the central circle (7). Traveling from 1 to 6 requires a transfer at 7. As mentioned, Brandon’s bus system is unicentric, though in Brandon the routes look more like getting to 1 from 7 requires going through 4, 5, and 6. It might be quicker to walk. Unicentric systems are great for people living closest to the centre, but the service gets worse further away.

For the polycentric model, routes run in both directions around the outer ring, from 1 to 2 to 3 to 4 to 5 to 6 and back again to 1 (and also reversely 1 to 6 to 5 to 4 to 3 to 2 and back to 1). Other routes go 1 to 7 to 3; 1 to 7 to 4; 1 to 7 to 5; 2 to 7 to 4; 2 to 7 to 5; 2 to 7 to 6; and in reverse. To get from any centre to the next, the bus needs only to cross at most one additional centre. If every route has two buses, one in each direction, the entire system will need at least fourteen buses running at any given time. In this imaginary polycentric city, it’s possible to go directly from any place to the other without transfers or layovers8. Polycentricism informs the proposed remodelling of Brandon’s transit system.

Brandon’s Urban Villages (or Centres)

A city is a cluster of urban villages existing within a greater whole. These centres need to be compact, have a high population density, and be highly walkable, and contained within a radius of roughly 400 metres to achieve the critical mass needed to justify a highly functioning public transit system9. In decentralized sprawling cities, like Brandon, it takes some imagination to identify centres. They are not compact, diverse, or population dense — with the exception of the historic downtown, which has been in decline for twenty or thirty years. Important high traffic areas with an abundance of underutilized space exist, like malls, the hospital, and the college and university campuses. Many of these spaces have a population density of zero and contain vast expanses of underutilized spaces in the form of parking lots. The shopping mall becomes a dead zone after closing time, other than the cleaners. Continuous activity, i.e., people on the streets, makes a city vibrant and feel safe. In a successful urban village it’s normal to see people out and about throughout day and night due to the mix of uses, high population density, quality public spaces, and the absence of cars.

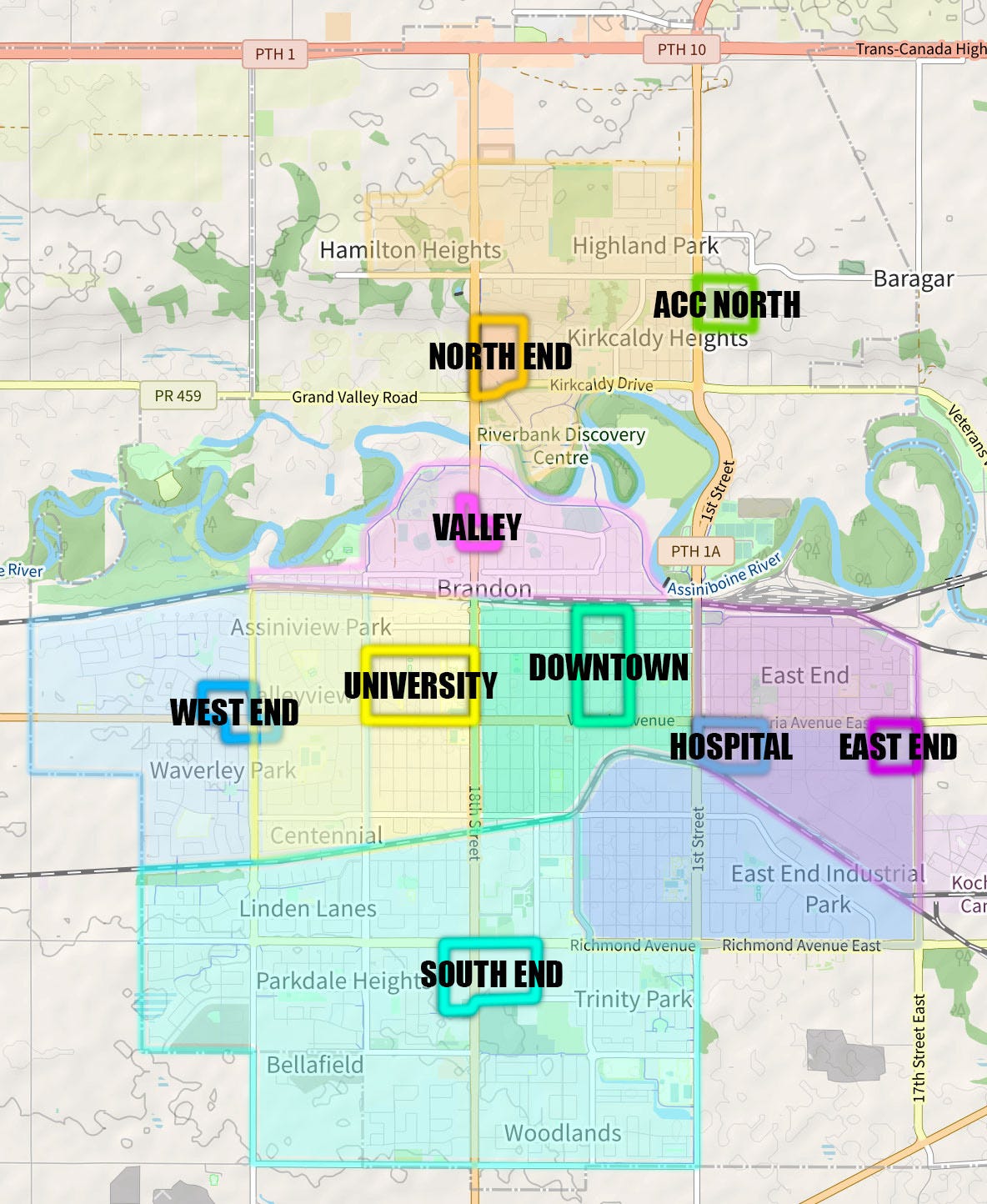

Above is a map of Brandon divided into centres. Each centre is connected to one or more of Brandon’s major arterial roads that provide direct routes to other centres. The smaller, outlined areas on the map mark the approximate boundaries for each centre, and the surrounding similarly coloured areas remain as suburbs where small scale organic farms can be established to support the self-sufficiency of the city, bringing healthy, ecological food production closer to the people — necessary as climate change worsens and food insecurity grows.

Other centres are likely to emerge over time if population density and diversity increases. Somewhere between the West End and the South End could be another centre, but currently the area is strictly residential and lacks continuous open space for the establishment of a centre. The Keystone area is another potential centre, but for the time remains an important and well connected stop between centres. Some of the suburbs overlap, like Hospital/East End and West End/University. The purpose of colour coding the suburbs is merely to illustrate which centre suburbanites are more likely to gravitate toward. Where there is an overlap, they could go either way.

ACC North is a recent development. Splitting the college into two separate, relatively isolated campuses has created some problems. ACC North is on the grounds of a former reformatory for boys and insane asylum that was purposefully constructed outside of the city10. Nothing is within walking distance. It sits on top of the valley and is fenced off by a highway without pedestrian or bicycle specific infrastructure to support safe access. Staff and students who want to go to a restaurant for lunch or run an errand will go by car. Those who need to travel quickly from from one campus to the other between classes have no other option but to go by car. A direct bus line running between campuses would provide an alternative. In some cities colleges and universities share a campus, the possibilities of interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary studies, and collaboration between academia and trades happen more spontaneously that way. Between BU and ACC there are about 6,500 students. The high levels of activity on a combined college and university campus would create opportunities for additional uses, especially restaurants, cafes, social houses, and public transit connections, had the long term spatial planning of the post secondary education focused on integrating the college and university campuses into the urban fabric of the city. Perhaps all of ACC will one day move to the North Hill location and the central anchor of the East End Centre will no longer be present. The hospital would then serve as the centre for the eastern part of the city.

Brandon University is better situated than ACC, not far from the downtown. BU’s Campus Master Plan expresses a desire to improve walkability, public transit connectivity, and reduce the presence of cars on campus11, but just as a city will be overrun with cars unless it’s connected to a well functioning regional transportation system, a neighbourhood (or campus) alone won’t have decent public transit connections unless the rest of the city does. The city and region need a transit plan to match the university’s ambitions.

The North End Centre and Valley centres are situated on a flood plain and are under a constant threat of flooding, especially as climate change worsens, and are costly to protect. In 2014 heavy rainfalls in early June flooded the Assiniboine River and caused over a billion dollars in damage. It was the first time on record that rainfall flooded the river. It’s always been snowmelt. I can’t deny the existence of the Corral Centre and the other buildings in the North End Centre and Valley. It’s important to stress that building in a flood plain is always a bad idea. Grand Valley, a neighbouring town, was built in the valley and destroyed by floods in 1881 and 1882 — a cautionary tale for future flood plain developments. Scaling back on development and creating a nature preserve in the valley is the best course in the long term.

There are three major regions of Brandon that pose some difficulty in creating an effective transit system. The north and south dividing line of the CP rail almost makes Brandon into two towns divided by the distance of the wide valley. The Eastern part of the city (not shown on the map) is a highly dispersed industrial site and has lower air quality lower, impacting the health of people at the East End Centre. The East End is not an ideal place for living, unless Brandon deindustrializes. These are a few examples of the dynamism and uncertainty of the city’s future. Looking at the geological history and forward to mass glacial melting, Brandon may even become a coastal city nearly drowning in the reawakened ancient river delta it sits upon.

Transforming Asphalt Expanses Into Urban Villages

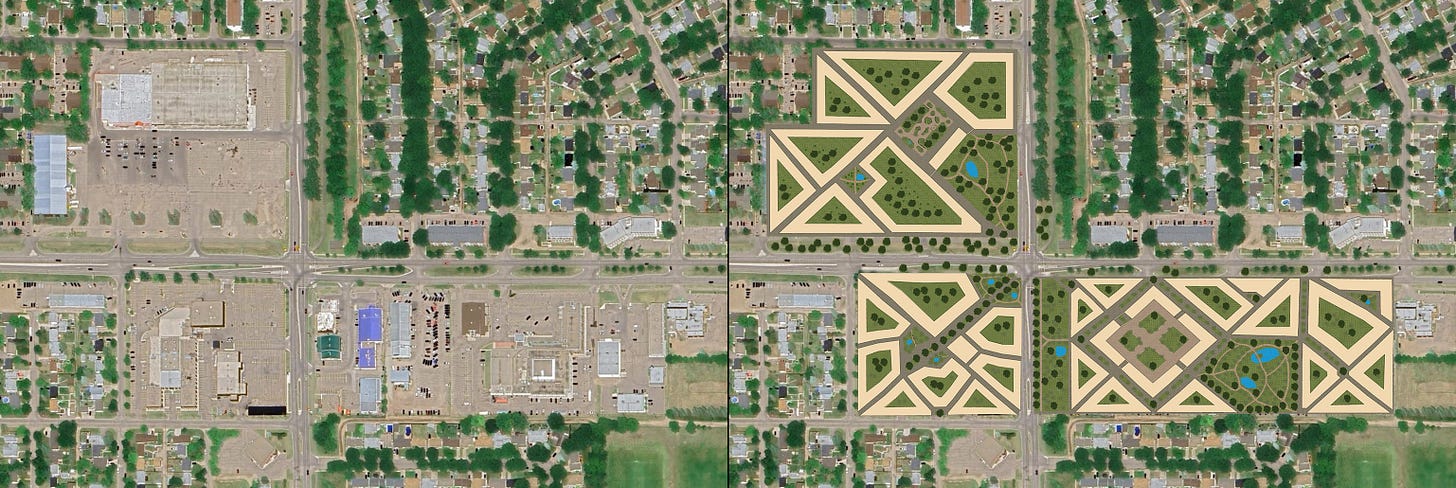

The above image shows the current parking lot expanses of the West End Centre on the left and, to the right, a compact, diverse, population dense, car free neighbourhood design, inspired by green versions of the pedestrian zones of Oldenburg (Lower Saxony, Germany), Groningen (Netherlands), Gothenburg (Sweden), Pézenas (France). The yellowish shapes represent building blocks. Inside most of the blocks are common courtyards, semi-private spaces for the the local residents. Public parks, squares, plazas are situated throughout with leisurely walking paths, spaces for community functions, gatherings, ponds, trees, and open areas for picnics and social gatherings. Surrounding the plazas should be a small organic and package free grocery stores, daycares, clinics, cultural centres, cafes, and restaurants, the living rooms of the centre. The upper floors and the main floors outside the plazas are residential apartments and row houses. The buildings should be two and a half to six floors high to support a significant population density while retaining human scale. The triangular shape of the buildings increases the ease of walking by shortening distances, inspired by classic urban designs like Washington, DC and Paris. The irregularity of the building’s shape favours heritage construction methods.

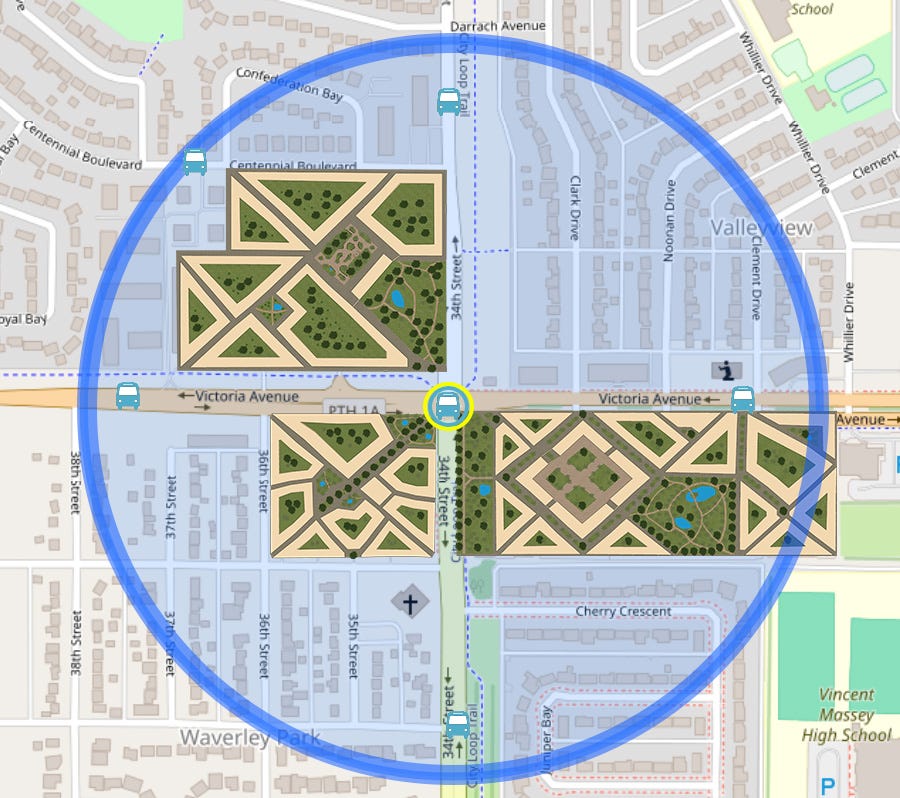

West End Centre is roughly 18 hectares of space. If 75 dwellings can be placed on each hectare and 2.5 people live in each dwelling, there should be about 3,375 residents. Since the core area has no cars, a well functioning public transportation system is necessary, though walking and biking remain options. The main transit stop with connections to the other city centres is located at the Victoria Avenue and 34th Street intersection, as shown on the diagram below, with secondary stops roughly every 200 metres along routes. Victoria Avenue and 34th Street are both four lanes. During the transition from car dominance, two lanes can be dedicated strictly public transit lanes. Eventually lanes can be removed and replaced with bicycle streets once cars are fully banned.

There is still much more to write about the design elements of the proposed West End Centre and the other centres; an in-depth description of a city-wide public transit system connecting Brandon’s centres; and what a Southern Manitoba regional public transit system could look like. The purpose of this post is to argue against the existence of cars, describe the ideals of an urban village, and provide an sketch of one possible scenario for the West End Centre.

I’m sure business owners and employees will be none too pleased to see their businesses and places of employment scrubbed off the map. Others might be excited by the prospects of car free, pedestrian friendly neighbourhoods with quality public and green spaces. I want Brandonites and people in similar cities to think critically about the spaces within their city and advocate for neighbourhoods compatible with decent public transit, active transportation, good health, climate action, and ecological sustainability, and especially to turn underutilized urban spaces (such as parking lots and box malls) into vibrant spaces to meet the pressures of population growth without expanding the spatial footprint of the city. Local governments and activists need to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and ecological damage. Weening people off cars, advocating for car-free neighbourhoods and quality public spaces are ways of achieving those goals while improving the quality of life.

After attempting to winter bicycle without studded tires and wiping out on black ice one always immediately, I decided the next year to get winter tires and biked everywhere in Brandon after that, but I’m not everyone. It would have been nice to have access to effective public transit. Sometimes I waited for the bus, but it never came. I admit I drove my mom’s car sometimes — but rarely for trips in the city after I started all seasons bicycling, unless to go to Winnipeg or camping. Regional public transit is a topic I will take up in a later post.

Inadequate bus systems also push people into walking or bicycling, but the decision to drive, walk, or bike is shaped within the prevailing car culture. Other Brandonites I’ve spoken to have said that they would like to bike more often, but they feel it’s far too unsafe. They are worried about being hit by a car and drive instead.

See Free Transit Toronto and Free Transit Ottawa as examples of Canadian organizations advocating for free transit. For a list of organizations in other countries, check out: https://freepublictransport.info/organization/.

Greenhouse gas emissions statistics come from Climate Change Connection and I think they got the numbers from Statistics Canada: https://climatechangeconnection.org/emissions/manitoba-ghg-emissions/manitoba-transportation-ghgs/

Unfortunately I can’t find the CAA report. I don’t want to cite the National Post. The annual cost of car ownership comes from this page: https://www.cardealcanada.ca/costs-of-owning-a-car-in-canada/. Costs include insurance, car payments, fuel, and repairs.

Brandon Transit monthly fare is $86. Brandon University students have a special agreement with Brandon Transit. It must be higher now, but when I was a student at Brandon University, every student had to pay $15 on top of their tuition to ride on the bus unlimited for the year. Car owning/driving conservative students tried to protest the small fee, but failed. For information about the agreement, check out: http://www.busu.ca/u-pass.

Improving public transit should help cities and regions to become more accomodating for active transportation, too. Buses, trams, subways still need energy input, and requires space and materials and that still has an ecological impact. Collectivization reduces the demand for energy, space, and materials compared to individualized options, like owning a private car. Walking and bicycling have a lower impact than public transportation.

Noise pollution causes “cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and health-issues including sleeping problems, annoyance, and stress” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4358829/

A BBC article about the impact that noise has on the development of children: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240621-how-traffic-noise-pollution-harms-childrens-health-and-development

Air pollution causes heart disease, lung cancer, asthma, pre-mature death: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/apr/21/years-breathing-traffic-pollution-increases-death-rates-study-pollutionwatch

About the exposure to exhaust inside car cabins: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jun/12/children-risk-air-pollution-cars-former-uk-chief-scientist-warns

Light pollution cause cancer, metabolic disorders, mood disorder: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7764771/

Sleep disorder: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31342600/

Obesity: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959804922003549

Depression: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969722022781

Pollution from tires is worse than pollution from exhaust — this is also a problem for bicycles, buses, and shoes — but shoes and bicycles produce less: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/03/car-tyres-produce-more-particle-pollution-than-exhausts-tests-show

Car fatalities and injuries from Statistics Canada: https://tc.canada.ca/en/road-transportation/statistics-data/canadian-motor-vehicle-traffic-collision-statistics-2022

Cars and obesity study: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15261894/

Information about the urban heat island effect: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8543181/

A short video from DW about heat and mental health:

An example of a polycentric public transit system I’m quite familiar (after living in the city for almost two years) with is Gothenburg’s transit system. It includes trams, buses, and ferries. See maps here: https://transitmap.net/gothenburg-tram-ferry/

New Urbanism suggests 400 metres is the distance people are willing to walk before deciding to drive a car. Read about Pedestrian Shed here (idea number 1): https://www.cnu.org/sites/default/files/25-great-ideas-book.pdf

If you are interested in learning more about the history of the building, please read here: http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/brandonmentalhealthcentre.shtml. It probably would have made more sense to have been converted into a wellness retreat, although it overlooks the local prison — we’ll get to prison abolition in time.

Read the Brandon University’s plan here: https://www.brandonu.ca/campusplan/