Alleviating Car Dominance (Part 2)

Ideas for improving public transportation in Brandon, Manitoba (a medium sized city)

In a previous post, I laid out a few ideas about converting underutilized urban spaces into vibrant neighbourhoods. The purpose was to propose a city structure more conducive to public transit. Here I go into more detail about what that public transit system might look like. I want to reiterate my concerns about the spatial expansion of (sub)urban areas. Space on Earth is limited, so should the spatial footprints of cities be. How we use space needs to be carefully considered. Cities should find ways of meeting the demands of population growth by making use of underutilized spaces within the city rather than expanding outwards. Cars consume large quantities of (sub)urban space in the form of parking lots and streets. Removing cars from the equation, especially in car dominant cities, frees up large swaths of space, reducing, and probably eliminating, the need for outward expansion.

To summarize the five main principles from the previous post:

Urban neighbourhoods should be designed to accomodate an urban density of roughly 75 occupied dwellings per hectare.

Neighbourhood designs should focus on delivering plenty of high quality private, semi-public, and public spaces in the form of courtyards, plazas, squares, pedestrian streets, and parks.

Buildings should follow heritage construction methods using brick, stone, plaster, and wood, natural paints, and sustainable interior materials, like flax, wool, or cotton insulation — thinking in terms of the building’s life cycle and using materials that either biodegrade or are reusable without any negative environmental side effects.

Diverse uses should be embedded in neighbourhoods and all needs should be obtainable within a 400 metre walk, including access to greenspace and public transit with connection to the rest of the city and region.

Neighbourhoods should be entirely car free, meaning no parking spaces and no through car traffic. Mobility should mainly be achieved through public and active transportation.

In the previous post I defined the boundaries for eight centres in Brandon, Manitoba and drew up a design plan for one of these centres, the Westend. The design converts underutilized space, mostly parking lots and disconnected buildings, into mixed use neighbourhoods, filled with plazas, squares, courtyards, and parks following the five principles above. I didn’t go into detail about what the public transit system might look like within the Westend or how it connects to the rest of the city and region. In this post I illustrate a possible localized public transit system scenario that connect the Westend suburbs to its centre and then show what the core system for the city could look like with a brief preview of a regional system that will be developed later.

There are many possibilities when designing transit routes. It’s important to consider what works best for people — but it’s also important to remember that urban structure is designed indepedently of the people who experience it. Newcomers and the people of tomorrow will have to navigate the (unfortunately often bad) designs of the past. Something that may be protested today will be valued tomorrow. It’s crucial to mitigate the mistakes of the past and make good choices today that help create a brighter future for the people of tomorrow.

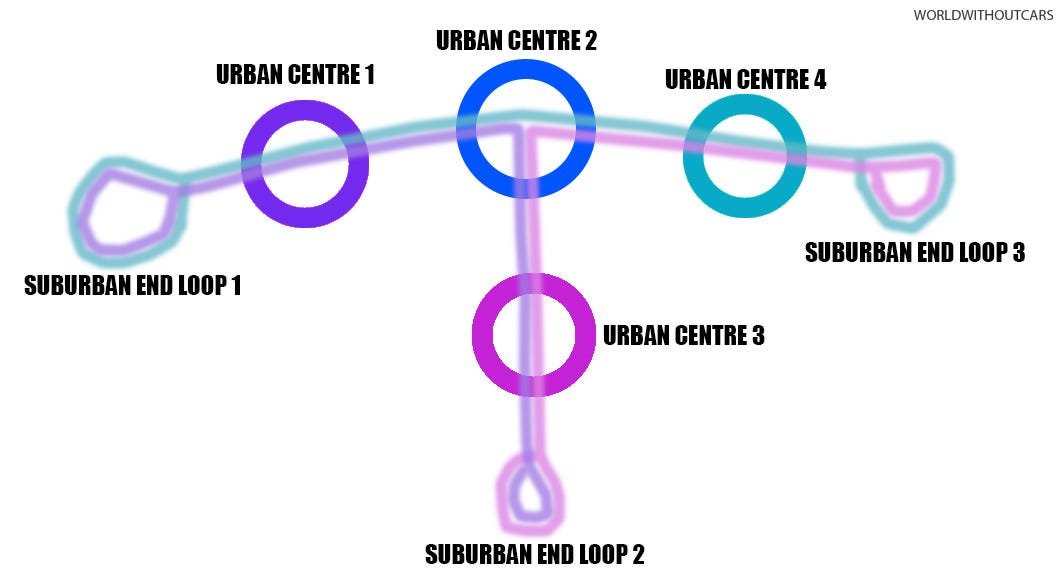

As explained in the previous post, centres should be connected by the most direct routes possible. Above is a basic illustration of a polycentric system. There are four centres, three routes (that make it possible to travel to any centre from any other centre without transfering), and three suburbs. At the last centre, the bus will need to turn around in order to restart the route. This can be done by making an end loop in the suburbs.

Unfortunately, the drawing doesn’t reflect the reality of the city. Brandon and similar cities have vast sprawling suburbs. In the Westend, an inclusive end loop would be more than 10 km on its own, dragging down the effectiveness of the route. Loops are unidirectional. A person who wants to get off toward the end of the 10 kms loop will have the longest bus ride, which would be unfair. The rider would probably be better off exiting the bus at the centre’s main terminal and walking the rest of the way.

A second scenario would be that buses alternate which loops they take, but that might lead to confusion and incidents of people being on the wrong bus at the wrong time. A third scenario is to seperate the end loops from the core routes, making transfering necessary. If there were only one cluster of suburban neighbourhoods, then it would have been possible to run the core route through, like in the diagram above, but there is simply too many suburban areas for that.

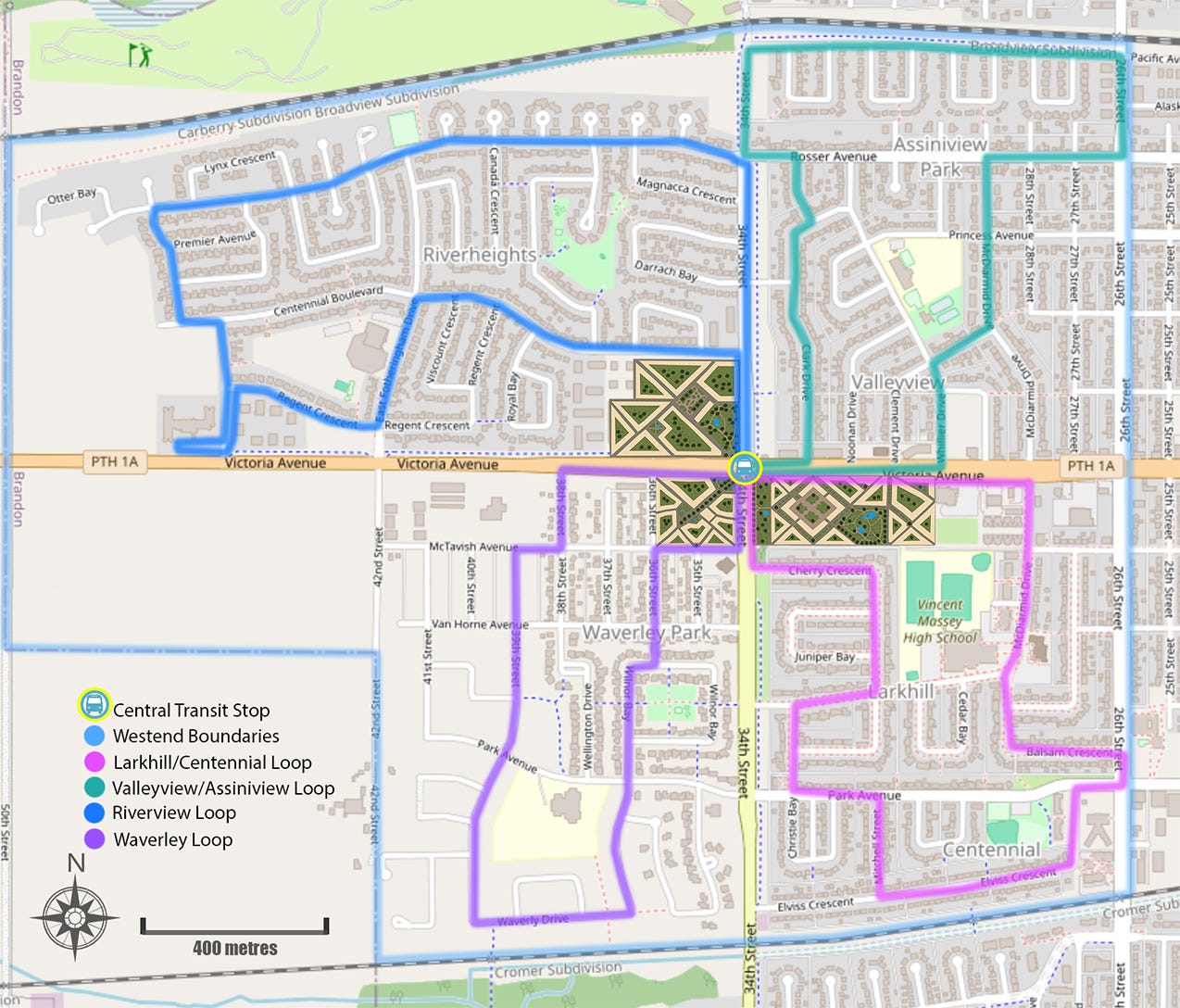

Above illustrates possible transit loops for the Westend. No dwelling is further than 400 metres from a bus stop — most are much closer.

The distances of the routes are:

Riverheights 4.6 km

Valleyview and Assiniview Park 3.8 km

Waverley 3.2 km

Larkhill 3.9 km

Each route should take less than 10 minutes to complete by bus, but it’s better to test the time than estimate it.

The inner centres, like University, Downtown, and Hospital require buses that operate independently of the main lines, bringing people to the core area and the centre’s central transit station (I’ll show how this could work in another post). End loops, like the ones illustrated above, can be combined to reduce the need for buses. For example, a bus goes from the Waverley loop into the Riverheights loop and back again. The system should be flexible, increasing capacity at times of greater demand, like at rush hour or during special events.

Keep in mind that these loops are threaded through each neighbourhood as we move onto the next section. I’ll colour in the gaps later.

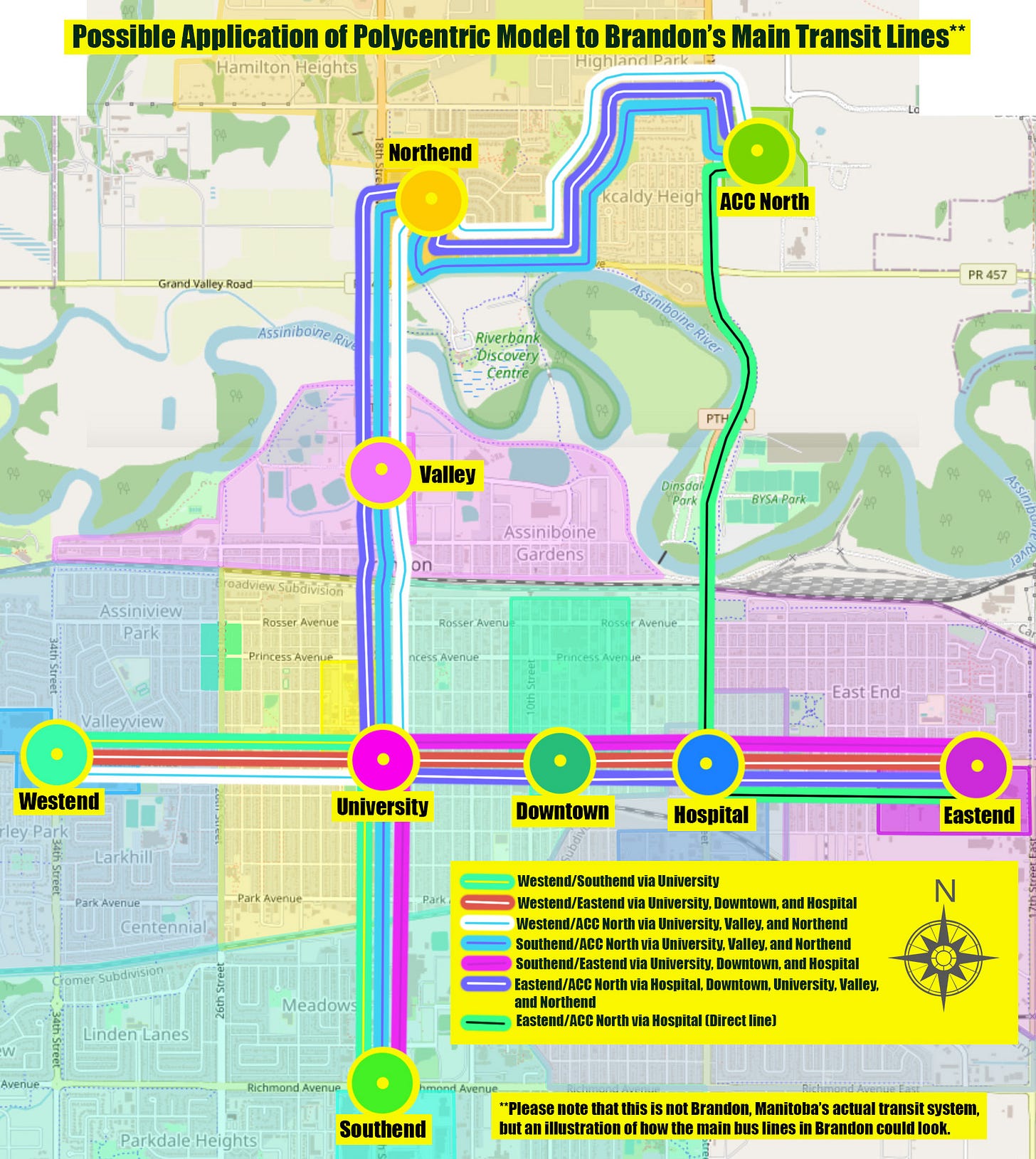

CONNECTING THE CENTRES: A POLYCENTRIC POSSIBILITY IN BRANDON

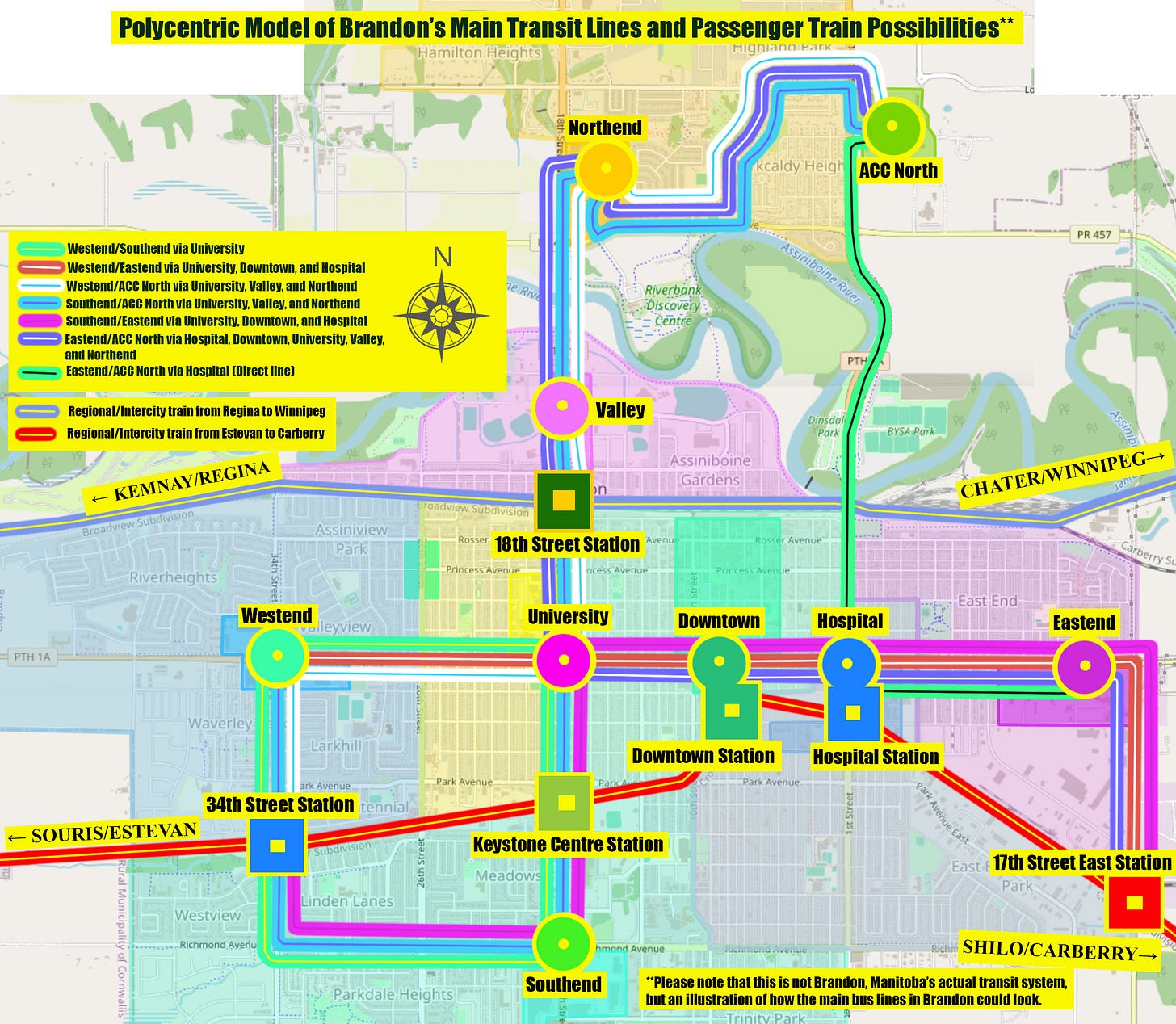

Each of Brandon’s centres are positioned along main arterial roads, Victoria Avenue, 18th Street, and 1st Street. Connecting centres via public transit is as easy as running bus lines along Victoria Avenue from 34th Street to 14th Street East, a trip that should take between 10 and 15 minutes — depending on how many stops are made. A route from Southend to Northend takes 18th Street from Richmond Avenue to the Corral Centre Mall, via University and Valley, which should also take 10 to 15 minutes. A seventh line is added to cater to the needs of ACC staff and students, taking them from the Eastend campus to the one on the North Hill, including Dinsdale Park. The image above illustrates the routes. Two lanes from 18 Street and Victoria Avenue should be dedicated bus only lanes, one for each direction.

In this design, Downtown’s central terminal is relocated from it’s current location at 8th Street and Rosser/Pacific Avenue to somewhere between 10th and 8th Street along Victoria Avenue (near Superstore) to minimize the lengths of the core routes. The University’s central terminal is placed close to 18th Street and Victoria Avenue for the same reason. That intersection terminal may need a special design to make the it functional. A drawing is needed, but I will save that for a later time.

Each centre’s main terminal has at least three core bus routes with the exception of Eastend, Hospital, and ACC North, which have four. Treat the map like a game. Pick a centre and a destination centre, figure out what bus you need to take to get there.

I imagine living in Brentwood again. How much easier it would have been to have a major transit station like the Southend one so close. Though it is still around 2 kms from where I lived, the land is relatively flat. It’s be an easy five to seven minute bike ride. It would have been getting to university easier.

I used to work as a substitute education assistant and was called to work at any school, sometimes with only 30 minutes warning. The furtherest from my house was Kirkcaldy Heights (about 8 kms). I biked it before and probably would bike it even if there was a direct bus route, but it would have been nice to have the option for when it was raining. I could bike to the Southend Station, lock up my bike there, catch the Southend/ACC North line, and get off at the Kirkcaldy Heights stop or the Sportsplex, whichever exists.

This is how I imagine most of the central stations would work. People who live close to them will walk (within 400 metres) or bike (up to 3 kms) to catch buses to other parts of the city. The localized buses running end loops and inner centre routes are there for those who are not walking or biking. When I was taking the tram in Gothenburg, I noticed people getting on at one stop and off at the one directly after it. From Redbergsplatsen to Stockholmsgatan, for example, which is a one minute tram ride covering 600 metres, a distance I would walk. But for people who are ill, mobility impaired, or have children with them, taking the tram for that short distance can be a relief. I should mention Redbergsplatsen to Stockholmsgatan is uphill.

A straightforward core transit system makes public transit much more accessible. Ease of use can persuade people to abandon their cars — which is needed to scale back on prevent further ecological decline. People won’t choose to be car free unless there is a regional public transportation system in place to take them out of the city. I’ve started on that below.

BEGINNINGS OF A REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN BY RAIL

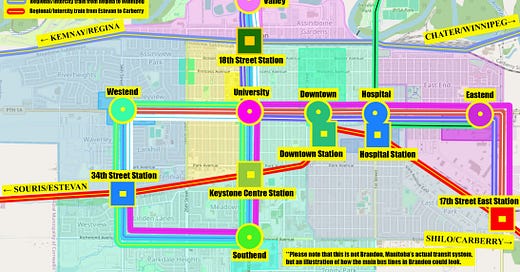

Above is the same map of the core system, but with the addition of regional rail lines. There should be buses coming from the north, south, and west. I will write seperately about the bigger regional picture.

Brandon has two rail lines running roughly east-west through the city. They connect to surrounding towns, villages, and cities. Before cars dominated the prairies, it was possible to catch a train from Brandon to Winnipeg and beyond. Today there are no passenger trains in Brandon. Not since the 1970s. The closest operating rail station is in Rivers, a 40 km drive from Brandon. From 1913 to 1932 Brandon had a tram system that extended as far as the Keystone Centre — the great depression doubtlessly played a role in its regretful end1.

My mom lives next to the CN line (on the map as Regional/Intercity trains from Estevan to Carberry) and mentioned that she noticed a strange passenger train rambling down the rails. This may be an indication that CN is testing passenger trains along that route. Welcome news, but I couldn’t find any information online.

The inclusion of rail improves options within the core system — though the tracks may eventually need to be doubled to improve travel in both directions. On the map above, bus routes are extended from the original system to integrate the rail connections.

The Estevan-Carberry line would bring people from the western parts of the city to the eastern parts, and it’s likely to be the quickest way across town, and the fastest way from Souris to Brandon, since the track cuts diagonally across the lanscape, unlike the highways. A new connection would have to be made at 49.78726137090826, -100.16575745441452 to allow for trains to switch tracks, a minor technical detail.

Westend commuters heading to the eastend would have a fairly direct line to work. Eastend factories are spread out, but most are connected by rail lines, so it is possible to create a commuter rail system for industrial workers. It should be coordinated with their schedules. This line would enable a person traveling from Souris or Shilo to go directly to the hospital, downtown, or the Keystone Centre without needing to take further transport — increasing the feasibility of living in a smaller town without a car.

It would have been a good idea to integrate plans for a rail station into the brand new $65 million 18th Street Overpass. A new overpass wouldn’t have been necessary if car use could have been curtailed either, but reduction is unthinkable under our dominant growth obsessed ideaology. The 18th Street overpass is a good location for a regional rail station within the framework of the proposed core system. It would already have buses with connections to every centre. Brandonites wanting to take a train to Winnipeg, Portage, or Regina (or somewhere in between) would be able to catch a bus to the 18th Street Station from any Centre and be on their way. The same with Winnipeggers or any guest arriving in Brandon. Buses would be waiting to take them where they want to go.

The 18th Street Station doesn’t need to be the only station along the CP rail line. Constructing a station on 1st Street or 34th Street is possible, but would require new core bus lines and more complicated system, unless these stations were to be left disconnection from the larger system, only serving people within the vicinity.

One of the best and most beautiful things about living in Manitoba is its national and provincial parks. Unfortunately these parks are unreachable without a car. Bus lines connecting Brandon to Turtle Mountain Provincial Park, Riding Mountain National Park, Duck Mountain Provincial Park, Spruce Woods Provincial Park, and the Brandon Hills Wildlife Management Trailhead should be created to accomodate day trips and camping. This is something that I will write about in a later post along with a closer look at the workings of each centre’s localized transit system.

Read about railway history of Brandon.

The old train station still stands today

For a brief history of public transit in Brandon, check out the Manitoba Transit Heritage Museum.

COME TO DETROIT 🙏